|

Associated G.P. Cinemas

© 1998, Bruce Peter

This article was first published in Picture House magazine in the Summer of 1998. This is the story of one of Scotland's most important independent cinema circuits and of its owner, George Palmer.

The George was the brainchild of George Palmer, one of Scotland’s cinema kings. Although his firm, Associated G. P. (which surprisingly stood for General Provincial) Cinemas was wound up only in 1983, all trace of Palmer’s business has vanished and his story at first proved elusive. I began by telephoning Janet McBain at the Scottish Film Council. ‘I once offered to interview his widow, but she totally refused - I’m afraid I can’t help you much this time, Bruce.’ Glasgow film enthusiast Ian Cunningham, who also helped with my Glasgow cinema book, actually met my subject in person. ‘I went often to the George in Barrhead. They had better than average pictures in there and, even in the seventies, never showed anything unsuitable for family audiences. I used to chat to the manager in the foyer and often I’d see a wee man in the corner, counting the audiences going in and chain-smoking. I asked who he was and was told in hushed tones that it was Mr Palmer… the owner. I chatted with him about the films and his cinemas. He was, of course, very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about the business with ‘hands on’ experience of all aspects of running cinemas. All that hard work must have taken its toll as by then he had baggy eyes and didn’t look at all well…’ George Palmer was born in 1903 in Govan, a burgh of Glasgow famed for its engineering and shipyards. He went to Govan High School and later to Glasgow Technical College, before joining Fairfields Shipyard as an electrical engineer.

Palmer set about winning audiences back from the rival Picture House by booking the best available films (during his brief spell at La Scala, he had made many useful acquaintances in the CEA and could often get new releases before the opposition). In March 1929, the Alhambra became the first cinema in Lanarkshire to fit talkie equipment (supplied by Western Electric) and Jolson’s The Jazz Singer opened there immediately after its record-breaking Glasgow run at the Coliseum. After seven years as manager, Palmer became managing director of the Alhambra in March 1932. In May 1937, Palmer acquired the Regal in Mossend, a linear mining village a couple of miles to the east of Bellshill . This was a conversion from the old Pavilion Theatre of Varieties, dating from 1912. Although the area was suffering from the effects of the depression, Palmer spent £4000 on refurbishment, including a new neon name sign on the frontage. At the opening, he was presented with a leather dressing case by Bill McGee, the Regal’s manager, who was to become one of Palmer’s most loyal employees as he built up his circuit during the following years. In 1938, the Alhambra was rebuilt and opened on 16 September. The Bellshill Speaker described it as ‘Lanarkshire’s New Wonder Cinema’ and explained how ‘Mr Palmer fully intends to bring London West End discipline into the Alhambra, which indicates that noise and drunkenness will not be tolerated. A rule that will be strictly enforced is that children in arms will not be admitted…’ The exterior was fitted with a full length canopy and a fin-shaped name sign, both with red and green neon. It made the Alhambra a landmark which could be seen from as far away as the platform of Mossend Station. The foyer had terrazzo floors, marble dados and an island pay box below a domed ceiling. The screen had two sets of curtains in crimson velvet over silver and gold silk screen tabs with French pleating. On the technical side, there was a new installation of Western Electric Mirrophoric sound apparatus (another first for the area).

According to Archie McNeil, who worked as a doorman in Palmer’s cinemas, his recipe for success was simple. ‘In Lanarkshire, cinemas were rarely short of audiences, and if they were doing badly, it was their own fault. Many of these places were just flea pits, in fact big circuits like Gaumont and Odeon were often the worst offenders as cinemas in what their head offices must have considered remote places like Coatbridge and Bellshill were the last ones to have money spent on them. You never were in such filthy, draughty places as the Bellshill Picture House or the Motherwell Pavilion, both old music halls. George Palmer, on the other hand, was always coming round in his silver Rolls Royce to keep an eye on standards. He insisted that the cleaners polish inside all the ash trays with Brasso!’ In 1940, Palmer was looking for fresh screens to conquer, but buying cinemas was a risky business then. He bought the Palace in Clydebank only weeks before it took a direct hit from a land mine in the Clydebank blitz. That hall had begun life as a variety theatre and was an original member of Maxwell’s ABC chain. Fortunately the audience had left for air raid shelters when the cinema was hit, although it was a write-off. Its proud new owner was unlucky to buy the only Scottish cinema damaged by enemy action. Undaunted, in 1942, Palmer more than doubled the size of his operation when he bought first the Pavilion cinema on the corner of Crofthead Street and Spindlelowe Road in Uddingston, in the shadow of the town’s main employer, the Tunnock’s bakery. The 850-seat Pavilion was a small and little-known ‘atmospheric’, designed by Albert Gardner and opened in August 1920. It was then described as ‘picturesque in the extreme and oriental in appearance.’ His other acquisition was far away from home (Palmer by then lived in Uddingston) in Portobello, a seaside resort on the Forth estuary which had been absorbed into Edinburgh.

The Bungalow was a rudimentary cinema with wooden forms in the front rows of a gas-lit single level auditorium with bare roof trusses. As Portobello’s Marine Gardens had been occupied by the Admiralty and there was a strong military presence, he re-named it the Victory. Palmer also bought the Central Picture House, an altogether more salubrious cinema in Portobello’s High Street. It had started life in 1915 as the New Picture House and had been run latterly by the same directors as the Bungalow. Palmer renamed it the George on 12 November 1942. A.J. Mullay remembers it clearly:

Its manager, Freddie Gardner, supervised all Palmer’s cinemas in the Edinburgh area. The cinema became a supermarket and fragments of the original interior are reputedly still visible above what is now a branch of Iceland.

Hard though it is to imagine, the interior was even more curious with a display case containing a Kilmarnock edition of Burns poetry marked as ‘A Gift for Whichever Leader Wins the War.’ The stadium auditorium was clad in faceted mirrors of different colours with a specially woven carpet glued to the ceiling - no wonder it was known as ‘Pickard’s Crystal Palace’. The reflections caused by the mirrors must have made watching a film at the Norwood very difficult! When the necessary building permits were obtained, Palmer had the Norwood rebuilt. There was a Gala opening on 14 August 1950 when the cinema was opened by the Lord Provost of Glasgow as the George. Palmer’s usual architect, Lennox Paterson from Hamilton, had toned down the interior, but the bridge remained until ABC took over in December 1955. The building is now a snooker club.

Palmer bought the Victory from the showman James Graham and after extensive refurbishment was carried out by Modernisation Ltd (a firm which inexpensively did to cinemas exactly what its name implied), it soldiered on until 1964. It then became a warehouse until demolition in the 1980s. Palmer’s various cinema interests were brought together when he formed Associated G.P. Cinemas in 1946 with an office at 149 West George Street in Glasgow. Its two directors were George Palmer and his second wife, Janet, reputedly a formidable lady, who was the driving force behind the firm’s continued expansion. That year he lost his pioneering Regal in Mossend to an overnight fire (Scottish cinemas burned down with unfailing regularity, perhaps because, especially in industrial areas, their patrons have always shown a macho disdain for the use of ash trays).

By the late forties, Associated G.P. Cinemas had become a large circuit, but although well maintained, the cinemas were a rickety bunch, mostly dating from the era of silent films. This situation was soon to change. In April 1946 Palmer bought the Ayrshire-based K.R. Blair cinema Circuit in what was then the biggest post-war cinema deal in Scotland.

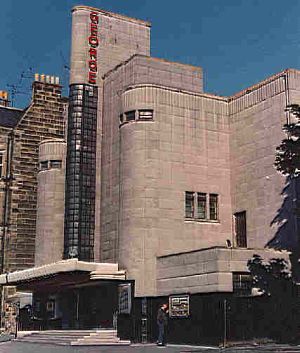

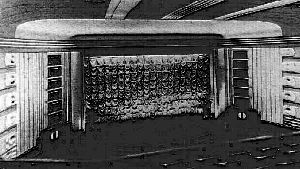

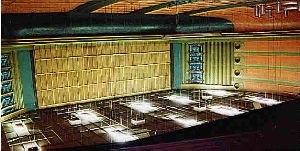

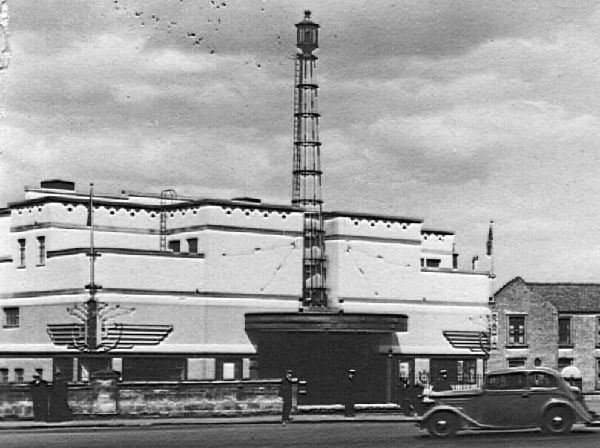

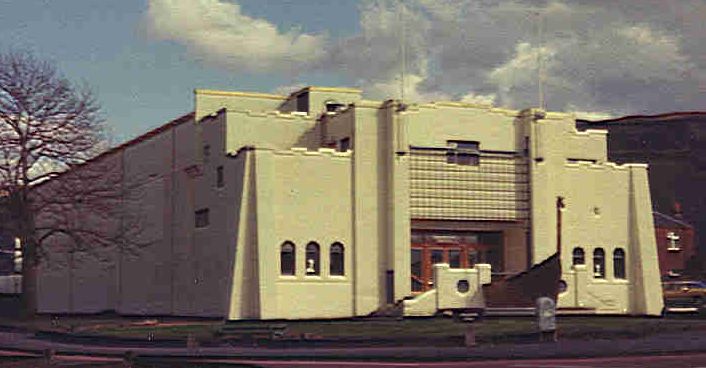

Radio Kilbirnie In the autumn of 1946 negotiations began with the Bridgend Picture House company to take over its four cinemas in Largs and Kilbirnie in Ayrshire. These concluded with a take-over by George Palmer in 1948. One of its directors was the Kilbirnie-based architect James Houston, responsible for the design of the two most flamboyant cinemas in the deal, the Radio and the Viking. The Radio was built in 1937 and, as with the somewhat better known Radio City Music Hall in New York City, took the mircale of electronic communication as its theme. It had a low, curvaceous white frontage with red and silver stripes, chrome eagle’s heads with wings at each corner and a mighty fake radio beacon soaring above the entrance with a flashing light and flashing purple neon zig-zags to broadcast its presence to the neighbourhood. Bearing in mind that the Radio stood at a cross roads in a staid little Ayrshire village of sandstone terraces and villas, this design was more than a little audacious! The foyer had a swirling terrazzo and mosaic floor which continued the theme of radio waves and the proscenium in its stadium auditorium was equally futuristic. The Viking was also themed, this time taking its inspiration from the Battle of Largs where the Scots trounced Viking invaders in 1263. It opened on 31 October 1939, ironically the day before another battle commenced as the Germans invaded Danzig. The Viking was a tour de force; it stood in landscaped gardens on the waterfront where a replica Viking long boat projected from the entrance. Patrons entered between buttressed walls beneath battlements and a portcullis which advertised the cinema’s programme and shut over the doors for security at night. The whole confection was painted in red, white and blue and there were murals showing scenes of the battle in the auditorium. Houston’s two cinemas were not only highly original, but also very convincingly designed. The other Largs cinema in the deal was the Electric Picture Pavilion, dating from 1911 and located up a side street next to the Gogo Water. Being tiny, badly appointed and remote from the town centre, it was sold to become the Star Ballroom in 1952, although miraculously it still exists. The last of the four was the Kilbirnie Picture House of 1922 which became the George for a time until it closed in 1959 and the Radio was given the circuit name.  Viking, Largs In May 1948, Associated G.P. Cinemas took over the Crown in Crown Street in the Gorbals - a densely packed area of slum tenement housing in Glasgow’s inner city. This 1930-vintage cinema, designed by Lennox and McMath, became yet another George and was one of the circuit’s busiest cinemas during the 1950s as it took the Rank release immediately after it had played in the city centre. It soldiered on until 1970 when its patrons were moved elsewhere by the city authorities to allow the much-needed comprehensive redevelopment of Gorbals to begin. On 24 November 1951 the George in Bellshill finally opened. Palmer’s dream-child and circuit flagship had been fourteen years in the making, but after much lobbying of the Atlee government by the all-powerful National Union of Mineworkers Lanarkshire Branch, the building permits were finally granted in 1948, although materials shortages had delayed completion by several more years. For Palmer, it was a triumph; the first brand new post war cinema anywhere in Britain and one of such high quality as to compete favourably with most city centre houses. The Ideal Kinema hailed it as ‘Scotland’s Contribution to Kinema Loveliness’ and ‘a Triumph of Beauty and Comfort’. The George had been designed by Lennox Paterson, and although the basic planning was pre-war, the latest thinking was employed in its execution. The exterior was a startling addition to the grimy streets of Bellshill, being clad entirely in cream, biscuit and black tiles with an internally-lit tower of glass block work at one end. The frontage was outlined in pink, red and blue neon with sixteen banks of white tubes under the canopy. The interior was equally striking. The entrance doors, without frames, formed a continuous expanse of armour plated glass to allow light to flood out into the street. There was a green and cream terrazzo floor with large ‘GP’ logos in mosaic and three concealed lights above. The circle foyer was panelled in walnut with an etched glass mirror frieze depicting local industries and transport in typical ‘Festival of Britain’ style. The auditorium walls were shaded in pink with intricate back-lit grilles, sprayed in silver, to either side of the screen and long troughs of pink cove lighting. The screen curtains were a memorable feature for there were three sets! First, the lights dimmed from the rear to the front and the grilles darkened. Then the vivid turquoise and green house tabs, with their colourful tropical fish, opened to the sides. Below, there were crimson velvet tabs with silver sequins. Once these slowly parted, a silver silk reefer tab scrunched up to reveal a vast screen. Cinema owners certainly knew about presentation in those days! The dark red carpet had interlocking leaves with the ‘GP’ motif and there wasluxurious seating for 1,750. Hugh Quinn was assistant projectionist at the George from its opening: ‘In

the days running up to the opening, Mr and Mrs Palmer arrived first

thing in the morning in their Rolls Royce, straight from home in

Uddingston, to supervise the preparations. Bill McGee, one of Mr

Palmer’s longest employees was manager, and as the days went

past, excitement grew. One night, they tested the neon lights outside,

which brought all the kids in the area out. There was a special, fully

illustrated opening programme with a silver cover, which was an

achievement with materials rationing still in force. The George had a

very spacious box with three Weststar projectors and WM 29 sound

equipment…

‘On the opening night, Mrs Palmer was to have performed the ceremony, but she couldn’t get the champagne bottle to break. Mr McGee tried smashing it on the door handles, but the audience just wanted to get inside because it was a freezing night. There was a grand reception upstairs with all the local councillors and everybody involved in building and equipping the cinema. The first film was a musical called The Toast of New Orleans…’ John Duddy, then a projectionist at the Rialto in Airdrie, was impressed by the standards set by the George: ‘The

George was the first cinema in Lanarkshire with CinemaScope and the

only independent with four track stereo sound. The team of

projectionists gave a flawless performance on the ‘miracle mirror

screen’, which was supposed to show the new wide process to best

advantage; it didn’t as there were obvious joins in the panels,

but the point was that the owners spared no expense in getting the

best. Sometimes, I was told, magnetic stereo prints were flown to

Glasgow at Mr Palmer’s expense. It was no mean feat for a

family-run cinema and a great stunt which none of its rivals ever

attempted.’

In 1954 with business booming, in an era still without mass access to television, Palmer bought another top class super cinema, this time in Portobello. The County was a striking moderne design by T.Bowhill, Gibson and Laing and had opened in March 1939 for Henry Paulo and Robert Scott (the former was of fairground origin and the latter was a local businessman). The County had a sumptous interior, although the balcony lounge in rich red tartan was perhaps not to everyone’s taste! Palmer intended that his latest acquisition should be a venue for Edinburgh Film Festival screenings, so it was refurbished to a high standard and, inevitably, re-named the George. It too was given tropical fish curtains, the ‘GP’ carpet, stereo sound equipment (the first Edinburgh cinema so fitted) and a re-styled lounge with a mirrored wall etched with a panoramic view of the River Forth. Its fine technical appointments secured an early showing of The Robe and each Festival season, it switched to continental films.

County / George Portobello

The era of the super cinema, particularly in provincial areas, was

drawing to a close with the advent of colour television. Even so,

George Palmer correctly believed that people would still want to go out

to the cinema for romance and spectacle in their entertainment. In

February 1969, when his fine George cinema in Irvine burned down, he

refurbished the smaller, older Palace in nearby Chapel Lane and it

became a replacement George. It was only a stop-gap as the site was

compulsorily purchased by the Irvine Development Corporation (Irvine

had been granted new town status) for an office development. Later,

Palmer took a lease on the abandoned Rex in Bank Street, a venerable

hall that had once been a Green’s Picturedrome of the famous

George Green chain. He spent £100,000 rebuilding it as the latest

George with a modern stadium-type interior with wall-to-wall curtaining

in gold. It opened in January 1976. In 1969, Palmer bought the derelict

Pavilion in Barrhead, near Paisley, for £80,000. It was a 1,009

seater dating from the 1920s and it was refurbished, opening as the

George on 11 April 1969 with Disney’s The Jungle Book. The

intention was to attract family audiences, but it was not a success and

closed in December 1977. Although Palmer offered it for sale to the

local Arts Guild for just £30,000, nothing came of the deal and

the George was demolished instead.Sadly, in the same period, the rest of Palmer’s cinemas closed one by one. The Viking in Largs, which had been part of the seaside resort’s magic for countless holidaymakers, shut on 4 August 1973 and was sold to local restaurateurs as a drinks bottling warehouse, although it has now been demolished. The flagship Georges in Bellshill and Portobello were both sold for bingo, the former to County Properties, whose owners were related to the original promoters of the Portobello cinema. The George in Bellshill continued as a cinema as repeated applications for a bingo license were refused. No money was spent on maintenance and it finally closed in 1982 for demolition. Its Portobello namesake went over to bingo, but despite grade B listed status, its interior has been carved up and its tower chopped down. The Radio in Kilbirnie lost its transmitter mast as a bingo hall and it now lies derelict. The Regal in Girvan became a Vogue bingo hall and the rest were redeveloped. George Palmer died in 1980, leaving his widow, Janet, to wind down the business. The two remaining cinemas were the Georges in Beith and Irvine, both in Ayrshire (the Palmers had retired to Largs where they had planned to open another cinema).

Many people reading this story will never have heard of Associated G.P. Cinemas. The Palmer’s operation was small compared with firms in the Home Counties, but their often remarkably-designed and always well-run cinemas brought a touch of glamour to the frequently dull industrial communities they served. George Palmer was an enthusiastic showman who made good through his love of the cinema. At the time of publication, Brian Wilson, the local M.P. for Kilbirnie and now also a cabinet minister, has set up a committee to plan the restoration of the former Radio cinema as a community centre. A Largs-based architect and art deco admirer called Paddy Cronin (of McMillan and Cronin) has been asked to plan the conversion. Given lottery funding, its tower will be replaced and it has been suggested that one day the building might even house a community radio station... [2006 update: the restoration of the exterior is now complete] |